click here for review list

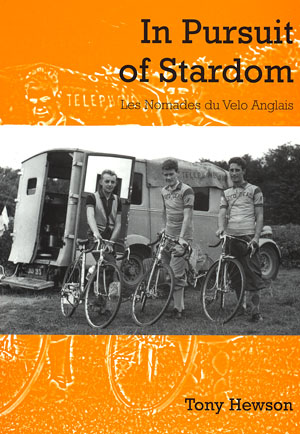

.........................................................................................................................................................................................................les nomades du velo anglais - in pursuit of stardom by tony hewson.

published by mousehold press £12.95 illus. 258 pages.

i think this may come under the heading of 'they don't know they're born nowadays' and not without good reason. in the days when the warring factions of cycle sport within the uk kept the number of competitive races to almost anorexic proportions, the only way for the young aspiring cyclist to fight his way to stardom was to get on his bike and go abroad. and apparently, very much like today, the standard and speed of racing on the continent was a lot higher than it was in the uk.

ironically, britons are enjoying somewhat of a rennaissance in europe at the moment, with roger hammond, steve cummings et al doing quite nicely thank you very much in either pro division or continental teams. but, not to detract in any way from their achievements, they didn't have to buy an ex world war 2 ambulance and have it kitted out as living and sleeping quarters before hopping across the channel, bikes and all, to 'have a go'.

but that's exactly what tony hewson, jock andrews and vic sutton did in 1958. fed on a diet of local races when they existed and copies of european sporting newspapers and magazines, and armed with a modicum of talent (hewson having won the tour of britain in 1955) the 'nomades du velo anglais removed themselves from uk shores to those of southern france to seek stardom 'behind bars' so to speak.

this incredibly wonderful book details almost every twist and turn of their years abroad, where fame beckoned, teased and offered by never quite let itself be caught. at least not in the sense that ullrich, pantani and armstrong achieved it latterly. nor, it has to be said, in the manner of bartoli, coppi and anquetil who were their contemporaries. the three nomades, however, did manage to race against their heroes and, very occasionally, beat them. they also were able to take part in 'le tour', and how many of us can write about that?

but, as is often said, it's not how you arrive, but how you travelled (or words to that effect), and in this case, the travelling was an adventure in itself. this book is quite brilliantly written - hewson has an unerring eye for detail, a very sharp turn of phrase ('belgian racing is technical in the way that crossing niagara on a tightrope in a force twelve gale is technical') and a wonderful way of organising stories into an eminently readable style.

It is quite seriously my contention that this book would be enjoyed by those who really coudn't give a monkey's about cycling. it is enthralling, adventurous, exciting and just plain funny, chapter after chapter. and rather than spending millions making a movie about lance, it would be a far better proposition to make a movie (in black and white) out of this. (does spielberg read the post?)

even if you've never paid any attention to my recommendations before (probably not without good reason), do yourselves a major favour and buy a copy of this. it is truly, truly wonderful and you will enjoy every word.

just as an addendum, if you'd like to order an autographed copy of this book, you can e-mail tony directly at tonyhewson@tiscali.co.uk

mousehold press £12.95

you can download a pdf of this book review here

..........................................................................................................................................................................................................excerpt from chapter 39

both the author and publisher have given me permission to reprint the following excerpt from chapter 39 of les nomades du velo anglais. the reason i'm re-printing this particular chapter is because i think it is one of the finest statements concerning contemporary cycle racing i have ever had the pleasure to read. i hope you agree

road racing is what really counts

And what of cycle racing, the passion that invested my every waking hour for thirteen youthful years? Abroad, it remains alive and well, and despite football's global domination and the damage done by drugs scandals, holds its place in popular affection. Yet poor recruitment at grass roots bodes ill for its future. Young people no longer come forward in anything like the numbers of fifty years ago. C.C. Saint Claudais long since went to the wall, typical of many small clubs unable to retain a viable membership. Even the once mighty BCR, founded in the penny-farthing era, is increasingly reliant on ageing veterans for its continuance. 'Young people nowadays want the easy life,' Pierre remarked to me in 1996, shortly before his death. 'Cycling is too tough.' He was right. Youngsters, ever more sedentary, succumb to the allure of computer games, junk food and 'soft' sports that eschew the full-time dedication and quasi-monastic lifestyle of the serious athlete. Moreover, to achieve the peak of physical fitness they have further to climb: people of my generation grew naturally fit and lean out of labour-intensive employment and having only their own two legs to get them about. Tumbling time-trial records, you ask? These are deceptive. They owe much to aerodynamic state-of-art bicycle and sportswear technology. Put the exceptional Boardman on an ordinary bike and even he struggles to surpass the World Hour Record achieved by Eddy Mercx thirty years before. The true barometer of decline is in athletics where our best male track and road middle and long distance runners operate well below the standards of earlier decades. Though Africans chip away at the London Marathon record, ever fewer homebased athletes achieve the once three hours' target of the good club runner. Sedentary life-styles, bad diets and obesity in childhood cast long shadows over the quality and appeal of athletic competition in the developed world. Good news, perhaps, for golf, darts and snooker, but bad for cycling.

In fact, for road racing in Britain, the news has been remarkably bad for some years. The sport suffers not only from a low media profile and, consequently, poor recruitment, but riders face training and racing in a traffic-bound, life-threatening environment. Confusingly, whilst the bicycle is repeatedly voted the greatest of modern inventions and successive governments advocate its health rewards, little has been done to counter the strident and intolerant propaganda of motoring lobbyists and petrolheads integral to the threat. Simply put, they want the bicycle off 'their' roads. From my observation, this highway war is a uniquely British disease, a nasty leftover from our class system and past failures to promote the sport. Continental motorists are much more respectful and tolerant of the velo. Why? Because over there the long tradition of cycle road racing has promoted the cyclist as an athlete, someone to be admired and entitled to his place on the highway, and not, as in Britain, an urban guerrilla or foolhardy pedal-pushing eccentric unable to afford a better mode of transport. Unsurprisingly, responsible parents think twice before encouraging their offspring to compete in such a hostile fearful climate.

It all looked so different in the optimistic, traffic-lite 50s. Writing in 1958 of Britons racing abroad, the late-lamented journalist, Jock Wadley, rosily prophesied: '...the determination of our 'caravanners' and other enthusiasts will one day surely mean Britain's establishment as one of the top road-racing nations of the world.'

The omens then certainly looked good. Ian Steel with his 1952 Peace Race victory set a marker. The Hercules team, on a steep learning curve, did amazingly well and Brian Robinson later became the first Briton contracted to a French team, and first to win stages of the Tour de France. At the amateur level, Stan Brittain was 1956 Olympics road race silver medallist and twice came close to emulating Steel's victory in Warsaw-Berlin-Prague. Our own venture by ambulance showed that the DIY approach to continental racing was a viable option and strong performances by Jock, Victor and Simpson inspired imitators. The formation of the BCF in 1959 brought unity and promise of further improvement. British riders featured regularly in the Tour. Hoban became a stage and classics winner, Simpson, Graham Webb and Beryl Burton world champions. There was such talent in depth: Booty, Geddes, Holmes, Sheil, Blower, Alan Jackson, Bill Bradley, Alan Ramsbottom (16th in the 1963 Tour), Vin Denson, Derek Harrison, Sid Barras and a host of others challenging at the highest level. Above all, the racing calendar back home was expanding and provided for all riders, professional down to third-category amateur. Take, for example, a typical Sunday in July, 1954 when the BLRC handbook featured 21 road races and compare this with the weekend of 3rd July, 2005 where BC offered a mere 13. There was a base from which to build.

Of course, we did not live in a risk-obsessed society and litigation fears were not the barriers they are today in designing courses. Light traffic enabled use of the whole road network, including the mountains of the Lake District, Wales and Scotland. The Circuits of Britain sponsored by Quaker Oats (1954-56) were amongst the toughest amateur events in Europe and gave riders like me a taste of long-distance stage racing through mountainous terrain, which proved invaluable when I transferred to France, something that short circuit racing can never emulate. Above all, we had political-savvy officials, the likes of Charles Messenger, Bob Thom, Vic Humphrey, Eddie Lawton, Dick Aldridge, Bob Frood-Barclay, Percy Stallard and others, people driven by messianic zeal to promote their beloved sport on a shoestring. There was also, at first, the spur of competition with the NCU (one wonders if unity without competition risks creating remote monopolies, a charge that has been levelled at BC?).

Fifty years on and there is little of Wadley's optimism left. To develop our young talent beyond nursery level, we must still export it abroad to learn the trade, partly on charity, the worthy Dave Rayner fund. At home, cycling generally rates in the public eye down alongside carpet bowls. To be fair, BC, formerly BCF, (one worries about an organisation in difficulty that suddenly severs the federal link with the past and rebrands itself as a monopoly. Why?) admits as much, but blames factors outside its control:

The profile of the sport isn't high enough (to attract rich sponsors) because the Great British Public are basically only interested in established British sports like football and cricket, or sporting events that take place in Britain (e.g. Wimbledon), or in success at the Olympics. (BC President Brian Cookson, LVRC newsletter 2003)

True, but that begs the question why, after 140 years, cycling isn't already an 'established British sport' when there is a bike in every home? Is it right to blame it all on 'the Great British Public'?

On the question of profile, it is well worth considering the structure of road racing abroad. The Tour de France is the flagship event commanding worldwide media attention. But the Tour alone could never support a full-time professional class. The Tour is the beating heart that feeds other organs of body cycling and receives vital sustenance in return. All the various national Tours, the Giro, Vuelta and lesser regional stage races, contribute, and, to continue the analogy, so do the arteries, veins and capillaries of the single day classics and thousands upon thousands of minor road races across the Continent, both professional and amateur. All are mutually interdependent and play their part, large or small, in keeping the sport alive and in the public eye. Continental cycling grew organically from around 1865 and with it the prestige, respect and media attention that today guarantee its influence with public bodies, such as governments, local authorities and the police. Above all, it is interlocked with community. (I can imagine no situation on the continent where a road race promoter would be told by a local police superintendent, 'We will have you off the road in a few years time', as has happened over here. The community would not permit it.)

British road racing has no body. That is the problem: no permanent race structure to speak of on the continental model, just a series of stuttering starts and stops. With no bankable tradition, low prestige and low expectations are inevitable (where would tennis be without Wimbledon?). Consequently, it enjoys little respect or influence outside the sport. Two opportunities to create such a body have been lost. In the 1890s F. T. Bidlake and his cronies surrendered to the horse and carriage lobby and abandoned road racing in favour of time-trialing. They touched the forelock and admitted to their lowly place in society. They could not possibly have foreseen the dire consequences of that decision. At a stroke it severed us from the Continent and all the benefits for cycling and cyclists here that would have accrued. It thwarted the formation of a professional class with eye-catching potential for a homegrown Tour and classic offshoots. It ensured that a huge amount of energy and talent was diverted into the publicity-free zone of time-trialling, where much of it still resides to this day. So began fifty years of divorce from community and 'meddling in cycling's affairs', the foolish separatist philosophy that Dave Orford, a community-relations exponent, bitterly dubs 'cycling for cyclists'. Then came our second opportunity in 1942. We all know the story, how Stallard and company formed the BLRC precisely to put Britain back onto a footing with the Continent and create a body cycling we could all be proud of.

The BLRC had real passion for road racing and it is tempting to wonder whether the outcome would have been better if it had remained in sole control and not been forced into the 1958 shotgun wedding with the NCU under pressure from the Home Office (the threat was to end negotiations on the right to race on public roads enshrined in the 1960s Highways Act, thanks to the BLRC). Typical of the infectious NCU strand of early BCF thinking was promoting Britain’s first ever stage of the Tour de France fourteen times up and down the wretched Plymouth by-pass: it was the mentality of the 1930s' closed circuit. The Tour of Britain's lost years, the demise of televised city centre criteriums and our World Cup Races have been damaging, whilst entrepreneurship (evinced by flagship race promoter Alan Rushton) seems, for whatever reason, to have run into the buffers. In 2003, the correspondence columns of Cycling Weekly were deluged with complaints of BC - publicly funded with a stream of salaried officials to do its bidding - turning its back on road racing and the grass roots.

Abroad, doughty Britons - Wegelius, Wiggins, Hayles, Hunt, Winn, the immensely talented Hammond and others - still fly the flag, but none since Robert Millar has looked likely to fill a top spot in the Tour or become points winner in the Vuelta (Malcolm Elliott 1989). We can all laud the splendid achievements of Yates, Boardman and David Millar, time-trial specialists who captured the yellow jersey. But the first two are now history, and Millar about to attempt a difficult come-back from a drugs scandal. And none was a great climber, for it is in the mountains where the Tour is won and lost. Out there somewhere in the general population, languishing undiscovered, may be our own all-round Ulrich or Armstrong. The question is whether he would ever be recruited into a sport like cycling with its lack-of-image problem.

BC claims to have the answer: to by-pass the road. It will focus on and recruit to the track, 'the more controllable and predictable environment'. It cites the example of Australia where ‘currently successful road professionals O'Grady and McGee began their careers on their country's track squad, and it claims early success here 'in the form of (track stars) Bradley Wiggins and Rob Hayles - both now members of Division One pro road teams'. That was two years ago, and for two years, and the first time since 1955, Britain has had no representative in the Tour. But we must give it more time. Professional roadmen have to serve a demanding apprenticeship and we should not expect too much too soon.

There are obvious flaws in this plan. Track and road are very different disciplines and it does not follow that success on one leads to success on the other. Former track stars tend to do what you would expect: they win sprint finishes and points competitions (yes, that would be nice!), but not, as yet, big stage races, where the climbers see them off. Also, too narrow a focus on track and circuit racing risks neglecting those with different abilities. Vic Sutton's forte was as a climber. He was no track or circuit rider. If that was where he had had to prove himself, I doubt he would ever have been discovered, much less selected for a national squad.

And there is another danger in the track/circuit philosophy. What is to stop some future track-struck administration abandoning the road altogether? We no longer need it, they may say. Let's negotiate away our right to race on the traffic-congested highways in return for the promise of funding to build a string of purpose-built circuits. Fanciful? Not at all! The chairman of the League of Veteran Racing Cyclists, speaking personally in 2003, advanced a similar solution to the problem. Oh dear! Abandon our birthright for a string of Eastways? A petrolhead could not have put it better.

It may come to that, but I would rather hang on to the slim hope of a miracle changing the climate for cycling in our crowded isle. What would it need? Profile is, indeed, crucial. Simpson was once a media ikon, BBC Sports Personality of the Year. His fall from grace left a deep scar on the image of British cycling. Now we need a second coming, a whiter than white high profile ambassador for the media to latch onto (a male version of gutsy Nicole Cooke?). Whilst, importantly, Olympic track successes produced a golden rain of funding, the publicity value proved ephemeral. Road racing is what really counts. Nothing, but nothing, could possibly match the immense prestige and political patronage that would accrue from a Briton winning the Tour de France. Dream along with me. Just imagine the scene: Blair meeting Chirac on the steps of the Elysee Palace, milking our victory for all its worth. Observe the smirk on that man's face as he puts one over on the French! Another Agincourt! Another Trafalgar! And imagine the aftermath, the doors that would open to cycling in Britain. Titter ye may, but, sadly, in my opinion, a miracle is our best hope for the future: our third and probably last chance to create a body cycling.

excerpted from chapter 39 of 'in pursuit of stardom' by tony hewson. published by mousehold press reproduced with permission.

..........................................................................................................................................................................................................this website is named after graeme obree's championship winning 'old faithful' built using bits from a defunct washing machine

..........................................................................................................................................................................................................as always, if you have any comments on this nonsense, please feel free to e-mail and thanks for reading.

this column appears, as regular as clockwork on this website every two weeks. (ok so i lied) sometimes there are bits added in between times, but it all adds to the excitement.

..........................................................................................................................................................................................................- equipment review: |fi'zi:k pave saddle

- clothing review | assos airjack 851

- clothing review | assos airprotec bibtights

- clothing review | rapha performance roadwear

- clothing review: |rapha performance roadwear - merino training top

- book review - spain - the trailrider guide

- book review - bikie

- book review - the yellow jersey guide to the tour de france

- book review - a century of the tour de france by jeremy whittle

- thewashingmachinepost colnago c40hp review

- book review: the official tour de france centennial 1903 - 2003

- book review: flying scotsman - the graeme obree story

- book review: riding high-shadow cycling the tour de france by paul howard

- book review: the ras - the story of ireland's stage race by tom daly

- book review: bicycling science 3 - david gordon wilson

- book review: one more kilometre and we're in the showers

- book review: food for fitness - chris carmichael

- book review: 101 bike routes in scotland - harry henniker

- book review: park tool big blue book of bicycle repair - calvin jones

- book review: roule britannia - william fotheringham

- book reviews: marco pantani - john wilcockson | lance armstrong - daniel coyle

- book reviews: a peiper's tale - allan peiper | man on the run, (marco pantani) - manuela ronchi

- book reviews: the tour de france - graeme fife

- book review: viva la vuelta - the story of spain's favourite race - adrain bell & lucy fallon